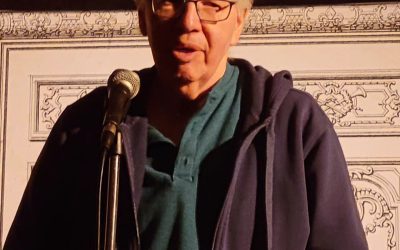

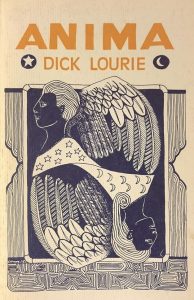

Dick Lourie lives in Chelsea, Massachusetts. He is a founding editor (1966) of Hanging Loose Press, a poet, and a blues musician. His work has been published widely for more than fifty years; his two most recent poetry collections, both from HLP, include:

**If the Delta Was the Sea, an exploration of Mississippi Delta history and culture, seen through his own experiences there as a working musician, and

**Jam Session and Other Poems, featuring an imagined dialogue between two old friends, Jazz and Blues.

Hanging Loose Press: What are this past year’s accomplishments that you are most proud of?

Dick Lourie: As with most years, I started off 2024 trying to balance (or at least juggle without too many slipups) writing, editing, and music. I have been able to spend more time writing than I did last year, mostly by being consistent, working on establishing the habit always difficult for me, but made some progress. I also started getting my desk and my study in order—made more progress on that than I’ve done previously. And I collaborated with my fellow editors in catching up with a heavy backlog so we could bring out two issues of our Hanging Loose magazine this year.

HLP: Yes, getting two issues in the same year is a mammoth job! What else?

DL: In book editing I’ve been proud of my work, again in collaboration with my colleagues, on Terence Winch’s It’s As If Desire, and Indran Amirthanayagam’s Seer. The two books demonstrate HLP’s openness to these two excellent poets of very different approaches and concerns. And with Joel Lewis’s Well You Needn’t: My Life As A Jazz Fan, one of the tasks Joel and I faced together was to make one coherent collection that would include both poems and prose memoir. I think we got it done, resulting in a really exciting book.

I’m still out there with the sax, blowing my top.

HLP: Any particularly difficult experiences/challenges for you this year? And how did you work through them?

DL: I just turned 87, and am correspondingly not so spry, let’s say, as I used to be. I’ve had a few challenges on that front this past year: getting around slower, trying to keep healthy. In general, though, doing OK for my years. To deal with it all, I’ve had to do some re-calibrating, getting out to fewer readings and, in particular, as a musician— since I’ve stopped driving—for getting to gigs. But I have managed to work around that, and I’m still out there with the sax, blowing my top. And on occasion (not so often as before) I can still play a chorus or two lying on the floor. But I will say lately it is easier going down than coming up, so now I get by with a little help from my friends. As we used to say, I just grin and bear it.

HLP: Yes, we could all take a page from that “grin and bear it” formulation! What are three books you’ve read recently that have made an impression on you?

DL: I’ve got a weakness for the Victorian and Edwardian novelists. I recently went back to re-read E.M. Forster’s Howard’s End. Published in 1910, it’s an extraordinary achievement, with a young woman protagonist and a brilliant look at politics, feminism, social class in England.

And The Sympathizer, a novel by Viet Thanh Nguyen, told in first person by a South Vietnamese army officer working for a general in exile in the U.S after the war, plotting to retake power. The narrator is actually a spy for the victorious Communist regime. It’s a chilling yet funny book; it won the 2016 Pulitzer. There’s a sequel (The Committed), but I haven’t yet worked up the courage to read it.

On the non-fiction side, I’ve really liked The Original Amos ’n’ Andy by Elizabeth McCleod. It’s an astonishingly well-researched account of the original radio serial (1928–1943), a widely popular program. The unlikely fact is that this tale of two young working-class black men migrating north from Georgia was loved by millions—black and white, and in its first decade never had fewer than fourteen million listeners a year—during one of the most vicious eras of lynchings and Jim Crow. And, just by the way, if you’re unfamiliar with the program, it was written and performed by two white men.

HLP: Yes, Jim Crow has a pretty long tail. But as for Amos ‘n’ Andy, I can see some whiffs of them in Sanford and Son, a show I used to watch as a child. Any upcoming projects?

DL: I have two projects for 2025. One is to try to do more readings. I’m not shy; I enjoy being out there, but I haven’t been very good at going out and arranging things. I’ve been working on the other project for a few years—now hoping to finish it up in ’25. It’s a book-length poem about radio. (The Amos ’n’ Andy book is one of my sources.) My own experiences with radio, my reflections, and the history of radio itself are woven through the book around a central narrative that describes and comments on the recording of a complete 19-hour broadcast day of a CBS station in September 1939. The recording, carried out in collaboration with the National Archives, is a vivid snapshot of mainstream America on the brink of war, but carrying on its ordinary life, for the most part unaware, like the characters in a Greek tragedy.

HLP: What are your thoughts on the rise of podcasts in relation to radio? Somehow a modern twist on the radio? Or something more akin to people’s desire to condense their information experience into increments?

DL: I don’t listen to many podcasts, but here’s my impression: they are certainly that “modern twist,” on radio (and also on TV). But radio has had its own twists. I remember hearing about “driveway moments,” when you had, literally or metaphorically, just got home and instead of going into the house you were sitting in the car listening to something you just had to hear. Now you can get rebroadcasts of almost everything, just as you can choose to get a podcast any time you want. Still, for radio you do need to tune in at a certain hour.

And, thinking back to earlier days of radio—as I’ve been doing for my poem—remember that, for many, listening was a family gathering experience—since that was usually the only place there was a radio. Of course, that circumstance has been gone for quite a while.

Also, to have a radio station, you need a license, equipment, and access to the FM or AM radio band—leaving out shortwave (different setup, different aims). To do a podcast, at least as I understand it, all you need is a computer, a microphone, and Internet access, which makes things a lot easier. And this is where the podcast connects with your question about the desire for condensation of information experience into increments. The connection is the familiar attention span problem that has been brought to us by our civilization. You can get anything you want, as Arlo Guthrie used to say, any time, any place, on your phone, at your convenience.

And you can say anything you want—which is a good thing, yes. But then, receiving the podcast, any time 24/7, it’s tempting to be the kid in the candystore: maybe I like this one, or so easy to jump to that one. And I can listen to a podcast no matter what else I’m doing; maybe a bit distracted, trying to pay attention to two things. And of course you can do that with radio, too, so maybe this is all about how easy it is to access anything in the world in whatever micro-increments you choose. And we’d be off on another discussion; let’s save that for a different conversation.

I have two projects for 2025. One is to try to do more readings. I’m not shy; I enjoy being out there.